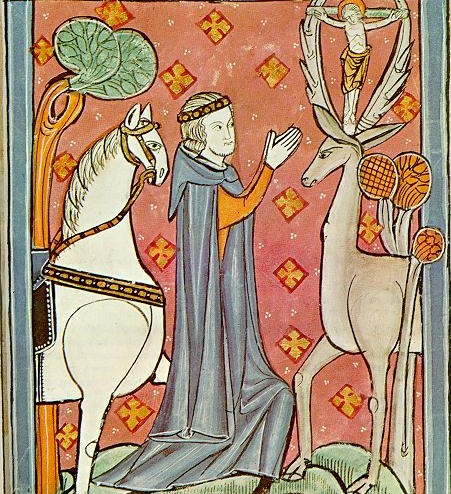

Ferns are unique plants in our ecosystems. While most of the plants around us reproduce through flowers and fruits, these adopt a different strategy, based on spores, which is now well known, but which remained enigmatic for a long time. This specificity, it goes without saying, was scientifically translated by the classification of ferns within an original taxonomic group, namely the division of Pteridophytes, which also includes horsetails and lycopods. But while we now understand how they work, ferns have long been a source of incomprehension. How could they reproduce without flowers and seeds? In the Middle Ages, for example, people did not understand why it was possible to find young fern plants, but never a single seed anywhere. Only one solution could explain this phenomenon: that the seeds of the fern are invisible. One deduction leading to another, since fern seeds were invisible, there must also be invisible flowers… which would therefore be capable – according to a logic quite typical of the time – of making invisible whoever found or consumed them (1) ! This was all it took for the popular imagination to unfold, and make the mythical fern flower a sort of plant Grail, an extremely rare marvel endowed with extraordinary properties. The fact is that the legend of the fern flower is extremely widespread throughout Europe, presenting quite astonishing similarities.

The fern flower across Europe

In fact, the fern flower is not perpetually invisible, for then it would simply be impossible to find. On the other hand, it only appears at a specific moment in the calendar, at a well-defined hour in the middle of the night, very briefly, and in a particularly remote and inaccessible place in the forests. One of the main common points in the legends relating to the fern flower is indeed its dated appearance. In the vast majority of cases, the famous night of flowering is that of Midsummer, or immediately before or after; in any case related to the summer solstice. The belief is particularly widespread in the northern and eastern countries of Slavic tradition, where the fern flower is said to develop during a night from June 21 to 24. This is the case in Poland, Estonia, Lithuania, Finland and Latvia. It is therefore linked to the celebrations of the solar cycle, of pre-Christian origins, but which have merged with the festivals of Saint John. In Finland, for example, we speak of the festival of « Juhannus, » or that of « Jani » in Latvia, or « Rasos » in Lithuania. It should be noted that in Poland, the fern flower could be observed not only at the summer solstice, but also at the time of the winter solstice (2). In any case, we understand that it appears on emblematic dates strongly linked to the influence of our luminous star.

While the belief is particularly strong in Eastern and Northern countries, it also exists in Western Europe. In England, it is said that on the eve of Saint John (once again), in the dead of night, the fern produced a single flower and that the villagers would then spread a sheet underneath to collect the seeds. No one ever became invisible, but the legend continued to be believed, to the point of performing rituals in the forest during the fateful night, until the church came to put an end to these obviously pagan practices. However, F.E. Corne mentions the testimony of a gentleman named Mr. Heath who, in 1779, still claimed to have participated several times in fern seed harvesting ceremonies during the nights of Saint John. And the man added that there were, however, disappointments, « because the fairies often stole the seeds » (3). Thus, we see that the fern flower is not a fantasy specific to Eastern countries. Moreover, what about the French tradition? Here again, we find local anecdotes or legends that refer to the concept. For example, Paul Sébillot tells us about traditions of this type, again linked to Saint John’s Day, in Lower Normandy, Touraine, and Brittany (4). He also attests to several songs and anecdotes evoking the harvest of the hypothetical « fern seed. »

Flowering always takes place in the middle of the night, never during the day. In many cases, it even occurs at a precise and symbolic time, and over an extremely short period of time. Thus, in Sweden, it blooms at midnight and immediately fades (5). The same is true in Polish traditions, where it is said to appear at midnight at the same time as a sound sometimes described as a crack, a crash, or a thunderclap is heard (6). In Lower Normandy as well, it blooms at midnight, and its seed must be harvested before it falls to the ground to benefit from its properties (7). A second later, the flower is no longer discernible (8). It is also at midnight that it can be found in Touraine, or at least it is at this time that it produces its seeds, at the same time as the clovers develop additional leaves to have four or five leaves (9). Furthermore, Paul Sébillot transcribes a very interesting Renaissance shepherd’s song: « In a bag the fern seed / That at midnight we gathered in the past / Denis and I, the eve of Saint-Jean » (10).

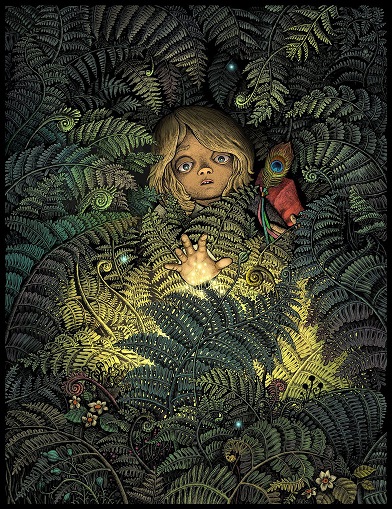

So now we know where and when to look for the fern flower, depending on local traditions and customs… However, we still don’t know what it looks like. What is it? The question is eminently complex, since its rarity makes it, by nature, a phenomenon never observed by most mortals. Beliefs in the fern flower attribute to it a multitude of characteristics, sometimes contradictory, but which generally make it an absolutely sumptuous spectacle. Thus, Slavic traditions imagine it to be red, gold or violet (11). In England, rumors rather evoke the birth of a pale blue flower, which quickly transforms into a golden seed (12). Reviewing the pictorial representations of the fern flower will convince us of its great heterogeneity: it can sometimes have five petals, sometimes many more; it can be imposing or on the contrary tiny; it can be found at the top of a long stem, but also be hidden under the leaves, at ground level; It can be palpable or resemble a phantom organ… Yet, the attentive observer will notice a commonality among all these images: the mysterious inflorescence is always depicted in a golden halo, surrounded by a dazzling glow that seems to burst from its petals. Does this stem from its unique relationship with the sun? Indeed, it is only visible in most legends at the time of the summer solstice. Of course, this detail also underlines its supernatural character. The fern flower seems to have sprung from another world, fallen from paradise, like a sacred relic protected by grace.

Such a treasure could only stimulate the imagination, and it is therefore not surprising that the fern flower is used in works of fiction. In addition to popular legends, we find books mentioning it, particularly in Eastern countries where it occupies an important place. The legend is mentioned in a book by the Finnish Aino Kallas, dealing with ancient folklore: The Wolf’s Bride (13). It is also cited by Andrus Kivirähk. In The Man Who Knew the Language of Snakes, the Estonian author mocks it, presenting it as a naive belief (14). In Poland, the fern flower is sometimes the subject of poems, such as that of Adam Asnyk (Kwiat paproci) some of whose verses can be translated as follows: « A strange fern flower blooms in the forests / For a moment in the mysterious shadow / The whole world is gilded with a magic light / But you can only touch it in your dreams » (15). Henri Pourrat, a French writer, collected the legend orally in Auvergne and transcribed it in Contes et légendes du Livradois, released in 1989 (16). Finally, there is a short animated film dedicated to the fern flower, produced by Ladislas and Irène Starewitch in 1949 (17). It features a little boy named Jeannot, who decides to go in search of the treasure on the night of Saint John’s Eve…

The Powers of the Fern Flower

As we have already touched on, the fern flower is coveted because it is believed to possess extraordinary properties. The most widespread of these is to bring its possessor incredible wealth. This is the most material version of the myth, which sees the discoverer living in abundance for the rest of his life, surrounded by jewels and chests overflowing with gold. For example, the fern flower brings fortune in Estonian traditions, but also among the Poles (18) and France. In Upper Brittany, it is said that fern seeds collected on Midsummer Night must be thrown onto a field to reveal the location of the treasures (19). In many legends, however, and as we will soon see in detail, the fortune gained is a curse, punishing the seeker’s greed.

When it is not specifically wealth that our mythical flower brings, it is more generally luck. This motif is also extremely common, from Russia to France. In Poland, it was sometimes believed that the fern flower was the Ophioglossum (Ophioglossum vulgatum). It was then said to bring success in love. In our countries, the ferns harvested on the night of Saint John, and a fortiori the hypothetical flowers of these ferns, were supposed to make you win at all games (20).

Here and there, the fern flower brings magical powers to the discoverer; extraordinary abilities that tend to blur the line between tale and reality. As mentioned in the introduction, since the fern flower is invisible most of the time, it has sometimes been assumed that it could itself confer invisibility (21). This is a way of thinking quite typical of the Middle Ages, and which is not without evoking the theory of signatures which states that a plant resembling an organ has an action on it (the liverwort, whose leaf shape recalled the liver, should thus be able to heal it). In any case, this property was attributed to the fern flower in Poland, but also to its seed in Lower Normandy. In Poland, it was also said that the fern flower could unlock any lock, but also bring clairvoyance to its possessor. This echoes another Norman rumor, which held that the seed allowed one to know the secrets of the present and the future (22). It has also been suggested that it gave one the ability to move from one place to another as quickly as the wind, or to speak to animals (23).

As a sexual organ, the fern flower is also a provider of fertility, and it has been used metaphorically to evoke carnal love. This point brings us to the symbolic implications of this mysterious treasure of nature which, far more than a simple popular belief, hides between its petals profound considerations about human nature and its vagaries.

Symbolic significance of the fern flower

First of all, and as we have just noted, the fern flower is in some places a symbol of love. Midsummer Night, placed under the auspices of the sun, has always been marked by the idea of encounter and seduction, as well as by fertility rituals that concern the earth, certainly, but also people. In the Baltic countries, young couples would go to have fun in the woods and it was said that they were going to « look for the fern flower » (24). In reality, it was a much less hypothetical flower that was picked: that of love. Moreover, it can be suggested that the true enchanted seed, growing from this famous fern flower, is allegorically the one that would, about nine months later, give birth to a new being. This night was indeed magical and, it was believed, propitious to procreation. From then on, the fern flower represents in some way the mystery of life; the primordial magic of existence and of the entire cosmos. A symbol of fertility, it’s no surprise that it gave its name to a Latvian NGO promoting sexuality education (Papardes zieds).

This conception of the mysterious inflorescence is still observed among Slavic peoples, where Midsummer’s Day corresponds to « Kupala Night » (25). Young people are seen there delving into the woods during the night, searching for the hypothetical « fern flower, » with girls wearing plant crowns in their hair. If a boy emerges from the thickets brandishing one of these, it means that the couple is engaged and that a marriage will soon take place. Here again, the fern flower takes on a metaphorical meaning; an allusion to romantic union and probably to carnal relations in nature. This tradition is in keeping with the holiday in question, since Kupala is an ancestral goddess of herbs and magic, but also of sex. Furthermore, linguists believe that its etymology may have a connection, albeit distant, with the Latin word « cupido, » meaning « desire » and relating to the well-known god, Cupid, who delivers his arrows of love into hearts.

But the fern flower is also and above all a symbol of the unattainable, like the mythical Grail so ardently sought and never discovered. It is the object of a romantic and passionate quest, where the journey and the trials seem to matter as much, if not more, than the treasure that motivates them. For, in fact, the fern flower is reputed to be impossible to pick, and even to observe. In Poland, it is said to be nestled in a remote and wild place, a thousand miles from any civilization, since one must not be able to hear the slightest bark of a dog there (26). Moreover, it is difficult to access simply because of its rarity. Often, legends imply that the fern flower is unique… Thus, the seeker would have to be precisely at the place where it grows, and at precisely the right time due to the ephemeral nature of its flowering; in Sweden, it is sometimes said that it only occurs at midnight sharp (27). It therefore takes a rather crazy set of circumstances to get one’s hands on this plant treasure. Worse still, some traditions believe that anyone looking for it has no chance of finding it, for the simple reason that it can only be discovered accidentally… or in dreams as in the poetry of Adam Asnyk (28).

As if all these insoluble parameters were not enough, the fern flower is often protected by supernatural means. In Poland, it grows in the heart of uroczyska, natural spaces endowed with magical power and generally linked to ancient pagan cults (29). It is also protected from various enchantments in Swedish legends, for example. In many cases, it is explicitly the forces of the devil that guard it, an idea found in the French countryside. Polish traditions often place it in places where witches roam, but also creatures typical of local folklore such as bies or czart (demons) (30). This explains the Christian venerations that, it is often said, must be practiced by anyone wishing to approach the fern flower. Prayers must be said, of course, but the adventurer must also have blessed artifacts, such as a rosary or a white tablecloth taken from the church altar. However, the rituals performed are sometimes much more bizarre and strange. It is believed that one can approach the mythical flower by arming oneself with mugwort and stripping naked (31). To take it with oneself, it is also said that one must absolutely forbid any backward glance, under penalty of suffering great misfortune; like Lot and his wife in the Old Testament, whom the angels formally forbade from turning around when Sodom is subjected to a deluge of fire (32).

From this, it is clear that the fern flower is a kind of plant Grail; an archetype of inaccessible preciousness, and consequently a passionate, mysterious, and unfathomable fantasy. But as such, it also embodies the dark side of dreams, like a symbol of the vain obsession leading Man to the fall. Like the sun burning the wings of Icarus trying to climb too high, the sacred inflorescence lowers the pride of those who think they are clever enough to pick it without fear. To illustrate this idea, traditions often specify that the fern flower certainly allows one to obtain fortune, but that it cannot be shared without it suddenly evaporating. The discoverers then see their family and friends sink into poverty, while they achieve a prosperous existence… but oh so unhappy. They suffer jealousy, and above all realize that, to paraphrase the famous phrase from Christopher McCandless’s notebook in Into the Wild, « happiness is only real if it is shared » (33). In some versions, the futile obsession with material wealth leads to an even more tragic outcome. We see the protagonist embark on his quest by denying his friends and family, cutting all ties with his humanity, and finally finding the fern flower deep in the woods. He then believes he is living in glory, blazing with wealth, then suddenly realizes what really matters to him and finally returns home. But of course, as expected, there is no one to welcome him back to his home village. On the other hand, he reads the names of those he loves on the crosses in the cemetery (34)… Here again, the fern flower is thus adorned as a cursed artifact, leading the greedy man to loss and suffering.

A vehicle for moral reflection, the legends of the fern flower often help to put the importance of earthly wealth into perspective, by drawing parallels with values such as friendship, love, piety, or spirituality. In a Polish oral tale, for example, there is a story about a young shepherd who loses a cow he loves very much in the woods. He naturally sets out to find it and, in the dead of night, so obsessed with his animal, fails to notice the strange flower he stumbles upon, a petal of which gets stuck in his shoe. Sumptuous visions then invade his mind, revealing hidden treasures and various paths leading to chests filled with gold. Of course, he also spots his beloved cow, and suddenly knows where to go to find it. He then returns with her and, exhausted, goes to bed, promising himself to go and find all the riches of his dreams the next morning… But at that moment, he takes off his shoe and drops the fern petal, which fades during the night and loses all its powers, making him completely forget in the early morning what seemed so clear to him the day before. The little shepherd, however, does not make a big deal of it, and that is the moral of the story: he has found his cow, and that is all that matters to him (35). A wise character, he knows that fortune would not have made him happier. Thus, through these few examples, we see that there is much more behind the fern flower than a simple imaginary treasure; it is an element rich in symbols, and among other things an incarnation of the vain and futile quest, of the thoughtless and pretentious obsession that distances one from appeasement.

***

The fern flower is therefore an absolutely fascinating motif in several respects. It testifies to human obsession with the unknown and mystery, and more generally with everything that escapes the distressing materiality of everyday life. It also shows the major role that nature plays in popular traditions, and therefore in people’s imagination and dreams. Moreover, the existence of fern flowers in both Slavic and English beliefs shows us once again the incredible cultural transfers that take place between peoples, even at a time still devoid of modern means of communication. Finally, the case of the fern flower also reveals the great diversity of interpretations that a simple myth can generate. The plant relic can be a romantic or sexual metaphor, but also symbolize the inaccessible and punish human vanity. It also reveals the divine fantasy that drives us, leading us to dream of magical powers, teleportation, invisibility, or animal communication.

However, could the fern flower be nothing more than a pure fabrication of the mind? Could it find no basis in the everyday observations of ancient inhabitants? We have already had the opportunity to outline an answer to this question, showing that the myth stemmed from a simple observation: that ferns did not produce visible flowers, unlike « classic » plants. Nevertheless, some pteridophytes sometimes display atypical organs, or exhibit shapes that could be likened to inflorescences. Thus, could the inspiration for the fern flower be the « spikes » of the tropic flower (Ophioglossum vulgatum)? This plant could be relevant due to its rarity. Could it not also be the fertile fronds of the German fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), forming upright clumps that the imagination can quickly liken to a strange flower? And what about those of the royal fern (Osmunda regalis), sprouting from the tips of tall, even more impressive stems? In this case, the species is entirely characteristic of humid forests, and could therefore be at home in the remote valleys described in legends…

Of course, all these questions will remain forever unanswered, and that’s undoubtedly for the best. The fern flower will always be a mystery, a fantasy, a marvelous belief in the minds of men, allowing them to escape the material world. Who knows? Perhaps it does indeed unfold in the heart of a dense and unexplored forest, somewhere on our Earth, hidden from view, during a few blessed moments of a summer night. In any case, it is certain that it blooms within us, in our heads and in our hearts, as do all our wildest dreams.

Pablo Behague, « Sous le feuillage des âges ». Décembre 2024.

**

1 F.E. Corne, 1924, Ferns : Facts and Fancies about Them : II.

2 Lamus Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower.

3 Corne, 1924, Ferns : Facts and Fancies about Them : II, op. cit.

4 Paul Sébillot, 1904, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France.

5 Gustaf Ericsson, 1877, Folklivet i Åkers och Rekarne härader.

6 Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower, op. cit.

7 Sébillot, 1904, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France, op. cit.

8 Louis Dubois, 1980, Recherches sur la Normandie.

9 Sébillot, 1904, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France, op. cit.

10 Sébillot, 1904, op. cit.

11 Brendan Noble, 2021, The Fern Flower – Magical Flower of the Slavic Solstice – Slavic Mythology Saturday.

12 Corne, 1924, Ferns : Facts and Fancies about Them : II, op. cit.

13 Aino Kallas, 1928, Sudenmorsian (La Fiancée du loup).

14 Andrus Kivirähk, 2007, Mees, kes teadis ussisõnu (L’Homme qui savait la langue des serpents).

15 Adam Asnyk, 1880, Kwiat paproci (Fleur de fougère).

16 Henri Pourrat, 1989, Contes et récits du Livradois.

17 Ladislas Starewitch et Irène Starewitch, 1949, Fleur de fougère.

18 Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower, op. cit.

19 Sébillot, 1904, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France, op. cit.

20 Sébillot, 1904, op. cit.

21 Corne, 1924, Ferns : Facts and Fancies about Them : II, op. cit.

22 Sébillot, 1904, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France, op. cit.

23 23 juin 2011, « Paparčio žiedo legenda – būdas kiekvienam pasijusti herojumi », Delfi.

24 Adam Rang, 22 juin 2022, « Fire, flower crowns and fern blossoms: Midsummer night in Estonia explained », Estonian world.

25 Ullrich R. Kleinhempel, 2022, Seeking the Fern Flower on Ivan Kupala (St. John’s Night).

26 Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower, op. cit.

27 Ericsson, 1877, Folklivet i Åkers och Rekarne härader, op. cit.

28 Asnyk, 1880, Kwiat paproci (Fleur de fougère), op. cit.

29 Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower, op. cit.

30 Dworski, 2016, op. cit.

31 Dworski, 2016, op. cit.

32 Auteur inconnu, VIIIe-IIe s. av. J.-C., Bible – Ancien Testament.

33 Jon Krakauer, 1996, Into the Wild.

34 Dworski, 2016, Polish legends: the Fern Flower, op. cit.

35 Dworski, 2016, op. cit.

You can follow my news on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sous.le.feuillage.des.ages/