Bryophytes, perhaps due to their small size and indistinct characteristics, have rarely captured the human imagination; certainly far less so than vascular plants. However, there are a few exceptions to this general observation, and goblin gold is a perfect example. Schistostega pennata, its scientific name, is indeed a truly unique species that grows on cave walls, in rock crevices, and even at the entrances to burrows. Calcifuge, it particularly appreciates sandstone or granite substrates, where it can be found in rock shelters, rugged cliffs, low walls, or along embankments, taking advantage of the refuges provided by roots.

But the fascinating nature of Schistostega isn’t solely due to its ecology, nor its preference for dark places avoided by other moss species. No, what truly makes it fantastic, and magical in the fullest sense of the word, is its ability to glow in the dark, deep within cavities illuminated by a flashlight or candle flame. Indeed, its protonema—that is, the layer of chlorophyll-containing cells that constitutes its first stage of development—is made up of tiny spheres that reflect incident light like lenses, thus appearing « luminescent, » an extremely rare property in the plant kingdom.

That being said, what will interest us in this article is not so much the phenomenon itself, but rather what it has sparked in the human imagination. Through its etymology, as well as through accounts of its discoveries and its cultural significance, we will explore the long-standing and worldwide fascination this species inspires. But let’s not waste any more time: let’s equip ourselves with a flashlight, good shoes, and a magnifying glass, and set off in search of goblin gold!

Etymology: Language as a Witness to Magic

Our little luminescent moss was first described in 1785 by Dickson, who discovered it in Devon, in southern England. The species was then named Mnium osmundaceum, a reference to a known genus (Mnium), but also, and perhaps more importantly, to the royal fern (Osmunda regalis), that beautiful, large fern whose pinnate tips were thought to bear a certain resemblance to moss. A few years later, in 1801, the species was renamed Gymnostomum pennatum by Hedwig, the name again referring to the « pinnate » leaves of ferns. Amidst a tangle of descriptions and new names, the name Schistostega pennata finally appeared in 1803. The genus name literally means « whose operculum splits, » and is unfortunately rather inappropriate since it does not correspond to what is observed in this species[i].

That being said, we saw in the introduction that what makes our subject unique is not so much the shape of its leaves or the opening of its capsules, but rather its protonema, which sparkles in the twilight. It so happens that for some time, however, this was considered a distinct species, and not a developmental stage of Schistostega pennata. Thus, in 1826, a certain Bridel described it as an alga he named Catoptridium smaragdinum. We find in this the Greek root catoptris, meaning « mirror » or « image, » and smaragdinos, which evokes an « emerald green. » In Latin, catopritis mainly referred to « a kind of precious stone, » an appellation which takes on its full meaning when one knows that the species shines like nuggets in the heart of caverns[ii]… However, it was only in 1834 that the truth was restored by Unger: this alga is not one, but is rather the protonema of goblin gold[iii].

The way we describe the things around us reflects our interest—or, conversely, our disinterest—in them. However, it is rather rare for bryophytes to have the honor of a well-established and widespread common name. As the reader will have guessed, Schistostega pennata is one of the species that benefits from this privileged treatment. Even better, our moss of dark corners has numerous common names, and even regional names that attest to a certain popular affection.

Often, its names refer to its luminous quality, either directly or indirectly. In the first case, the species is simply called luminous moss, luminescent moss, or shining moss, with all the possible variations depending on the language: for example, luminous moss[iv] or luminescent moss[v] in English; lysmose in Norwegian[vi]; leuchtmoos in German[vii]; Musco luminoso in Spanish[viii]… This luminous quality sometimes lends itself to more original, even amusing, names, such as rabbit’s candle[ix], which is said to be used in Scotland, in the Edinburgh area[x].

But the etymology of Schistostega pennata also extends into the realm of gold and treasure… generally associating it with folkloric creatures inhabiting caves and caverns. Of course, its most common name is goblin’s gold, which in France is sometimes translated as lutin’s gold. We find it in English, with the name goblin’s gold[xi]. That being said, our luminescent moss is also placed under the protection of the dragon, a creature of caves as well, but a much more frightening one. Among its English names is dragon’s gold[xii], which is also found in Sweden, for example, where it is called drakguldmossa, meaning « dragon’s gold moss »[xiii]. In any case, our Schistostega is frequently compared to a treasure… This is explained, of course, by its shiny appearance and cave-dwelling habitat, but also undoubtedly by its general rarity. The species is indeed scattered, confined to rather acidic areas, and exhibits a particular ecology that often causes it to go unnoticed. While it can be quite common in certain suitable regions, it remains a taxon that bryologists always find with a touch of emotion… something I can personally attest to.

The Thrill of Discovery

I remember my first encounter with Schistostega pennata as if it were yesterday. I was a young bryologist, still quite inexperienced, watching a wonderful, unsuspected world unfold before me: the world of mosses and liverworts, which I have never stopped exploring since. But if bryophytes are a fantastic universe in themselves, what can be said of this luminous moss, shimmering emerald green in the heart of hidden rocks; a natural treasure, revealing itself only to those passionate enough to venture into these seemingly useless crevices? That day, June 29, 2013, I had set out to explore the forests and streams of the Pays de Bitche, in Moselle, in the northernmost part of the Vosges Mountains (more precisely, in the commune of Sturzelbronn). Exploring the bryophyte flora of a rocky outcrop, I stumbled upon a small cave that plunged into darkness… It was then, under my magnifying glass, as I examined the species growing on the walls of the entrance, that I recognized the pinnate leaves of Schistostega. A smile bloomed on my lips, for it was a discovery for me, and it widened even further when, using my phone’s flashlight, I saw the emerald protonema gleaming in the dim light, a little further into the cavern… There weren’t many, just a few small spots here and there, but that was enough to make me happy. I found it very difficult to leave that place, for I had the overwhelming feeling of having unearthed a treasure; not a material treasure, but something far more precious, something to do with the heart and soul.

In the years that followed, I repeatedly came across the goblin’s gold during various outings in the Vosges Mountains, alone or with German and Alsatian bryologists. Each time, however, the sight of this shimmering species filled me with a feeling of euphoria, so much so that upon settling in the Vosges Saônoises region, I decided to resume my search for it, in order to better understand its distribution in my area. Considered very rare in Franche-Comté, the luminous moss is seldom mentioned in older literature and was then recorded in only two recently discovered locations. Armed with my flashlight, I scoured the landscapes, finally discovering it in several communes in the area. Sometimes I saw it shining in a cave, sometimes under the exposed roots of a tree on a bank… The same emotion overwhelmed me with each find, and when I looked into the accounts of the discovery of the species, I realized that this enthusiasm for Schistostega pennata was in fact widely shared.

Let us delve into some of these accounts, beginning with that of Anton Kerner von Marilaun. In 1863, in his work entitled Das Pflanzenleben der Donauländer (“The Flora of the Danube Country”), the Austrian botanist recounts the discovery of the species and justifies the legends and beliefs associated with it by its extraordinary properties. For when a fragment of this “gold” that glittered in the cave was taken, nothing remained in the daylight to convince us of its existence… In our hands, nothing but earth remained. Were we dreaming? Of course not, but the treasure possesses magical properties; we will return to this later. This, at least, is what Kerner von Marilaun says about it: “This phenomenon, that an object shines only in dark rocky crevices and immediately loses its luster in daylight, is so surprising that one can easily understand how the legends of fantastic gnomes and troglodyte goblins arose.”[xiv] We will not contradict him.

In 1921, G.B. Kaiser, an American bryologist, set out to search for the species in the Appalachians… The account of his discovery, which he himself provides in volume 24 of the journal *The Bryologist*, speaks for itself: “A cry escaped our lips!” Here, at last, lay the object of our search, the luminous moss: as our eyes explored the gloom, a faint glimmer seemed to grow and grow until it became the glow of « goblin gold »—a faint, yellow-green light that shone, sometimes steady, sometimes flickering, always exquisite, beneath our fascinated and delighted gaze. (…) Later that day, as we attempted to cross the edge of the woods to reach the rugged summit, the weather changed, vast expanses of cloud threatened us, and the wind blew mournfully: but we cared little for the coming storm! We carried in our hearts and minds a memory that would remain etched: we had succeeded in our quest, we had found the luminous moss, and even though since that day we have not been able to rediscover this object of so much wandering and wonder, this discovery led us to consider the word Schistostega as a magic word, a talisman, a lucky charm!« [xv] Thus, I am far from being the only one to whom this tiny moss brings comfort! Anyone who has the chance to observe it one day keeps within them a small treasure; a memory that is cherished and that accompanies us through trials like a blessing.

We could multiply the many more accounts of wonder relating to the discovery of our luminous moss, for example, by citing that of a certain Stephen Ward, who recounts his exploration of an area of Scotland dotted with rabbit burrows. As the light faded, he glimpsed something shining in some of the holes: “magnificent emeralds that sparkled, like a glimpse of a veritable underground Ali Baba’s cave,”[xvi] he explained. Thus, Schistostega pennata is frequently compared to a treasure. It is therefore no surprise that it is the object of a singular fascination—if not veneration—which is particularly evident in contemporary culture.

A magical and revered plant

Schistostega pennata is a small botanical talisman, a visual marvel that brings a certain joy to find. Even fans of the video game Animal Crossing may be familiar with this species without realizing it… There, it is called glowing moss in the English version, and can be harvested in New Horizons, on certain mysterious islands accessible only by boat. Once in the player’s inventory, this bryophyte can be used to decorate their house or garden, and also to craft items that will then possess a luminous aura[xvii]…

The presence of Schistostega pennata in a Japanese video game is not so surprising, as the species enjoys a veritable cult following in the Land of the Rising Sun. Furthermore, it plays a central role in a book that even lends its title to the story: Hikarigoke (Luminous Moss) by Taijun Takeda, published in 1953.[xviii] The book tells the tale of sailors stranded by a snowstorm on the island of Hokkaido. Finding refuge in a cave, they are ultimately forced to resort to cannibalism to survive. The captain, the sole survivor, explains in court that those who had consumed human flesh possessed a phosphorescent green aura around them, which only those who remained healthy could see. It is understood that the cave was inhabited by Schistostega. The novel was adapted into an opera[xix], and also into a film under the title Luminous Moss.[xx] In the film version, the protagonist is a writer who one day discovers a cave entirely covered in this moss, shimmering before his bewildered eyes. Having heard a story of alleged cannibalism involving a crew of sailors shipwrecked on an island, he imagines a scenario in which the flesh-eaters would be betrayed by emerald halos around their heads, a souvenir of the moss he had observed…

The fluorescence of goblin gold thus plays a sinister role here. But in Japan, it is also the object of more traditional veneration, to the point that a memorial is dedicated to it within a small cave located on the island of Hokkaido. Luminous moss covers a good part of the floor and walls of this cavern, where one can reflect and meditate, losing oneself in its singular phosphorescence.

We now turn to an archaeological mystery, which takes us back to Europe, and more specifically to England. In his book Bryophytes of the Pleistocene: The British Record and its Chorological and Ecological Implications, the scientist J.H. Dickson discusses a discovery that is nothing short of enigmatic… and extraordinary. He explains that a fragment of Schistostega pennata was identified in “the socket of an axe buried within a Bronze Age deposit” at Aylsham, Norfolk[xxi]. While it is already remarkable that the plant has remained identifiable after all this time, it is above all the location of its discovery that opens up fascinating perspectives. How did a fragment of luminous moss end up inside a weapon? Was it the result of chance or a deliberate act?

It goes without saying that, when studying materials from such distant periods, any attempt to provide definitive answers is illusory. Dickson opts for an accidental introduction into the handle, probably during the axe’s manufacture, and this hypothesis is indeed plausible given that Bronze Age tribes frequently gathered in caves that constitute the very habitat of our goblin gold. It should be noted, however, that the species is absent from Aylsham, and more generally from eastern Norfolk[xxii], and that, given the specific nature of its habitats, it is likely that its distribution has not changed much over time[xxiii]. This would therefore mean that the weapon was transported over a relatively long distance and was not manufactured where it was buried. That being said, while the possibility of accidental introduction into the axe socket is quite real, we cannot rule out the hypothesis of deliberate insertion into the tool. Was this species the object of particular veneration? Is it possible that magical properties were attributed to it, which would explain its presence in such a singular location?

Let us remember which species we are talking about: luminous moss, goblin gold. The mere mention of its name evokes fantastical tales, so how can we imagine that it did not also fascinate the people of old, who saw it shimmering in caves by the light of their torches? Dickson himself does not entirely dismiss this theory: « The possibility remains that Schistostega had a magical significance » [xxiv]. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the Celtic deities associated with fire are, in fact, also linked to the forge. This is undoubtedly the case with Belenos[xxv] and Bel, perhaps even with Lug. These too are solar deities, and therefore luminous gods, like our goblin gold protonemas. Let us now imagine our ancient craftsman, working on the making of weapons within some sandstone cavity, forging this axe over a fire that makes the surrounding walls gleam like gold… How could he not be troubled by such a phenomenon? Thus, perhaps Schistostega pennata was associated with solar deities, and therefore with the entities that governed the flames of the forge. Of course, we will never know for sure, but this fragment in the axe is nonetheless a highly intriguing element, opening up rich possibilities. Unfortunately, to this day, no similar discovery has been recorded.

The Ephemeral Gold of Goblins

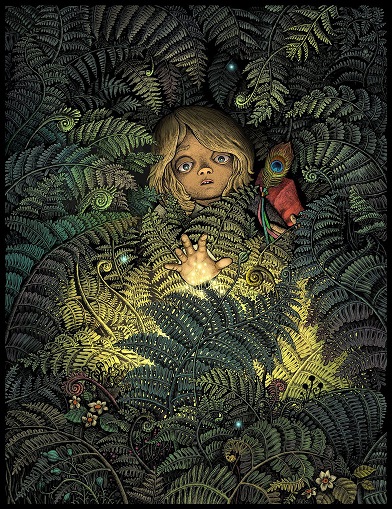

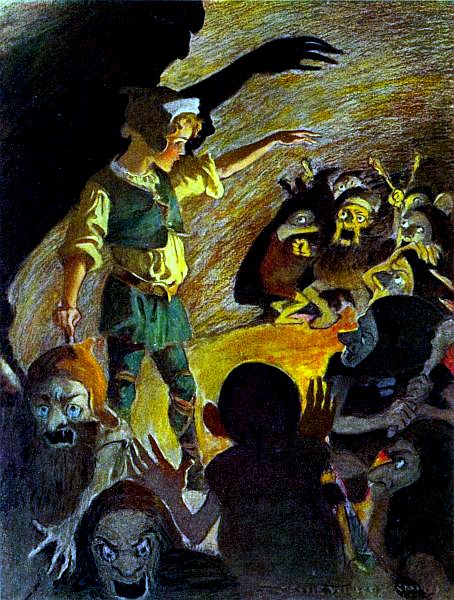

Thus, it is possible that Schistostega pennata stimulated the human imagination as early as prehistory. But our questions about it can easily be extended into the modern era. We have noted that bryophytes are rarely mentioned in imaginative works—no doubt due to their inconspicuous nature and their similarities to one another—but this does not mean that they could not have inspired certain motifs in our legends. In this case, Schistostega pennata, by its very etymology, is openly associated with subterranean treasures, and with the goblins who are often their guardians. Caves and caverns have always intrigued people, especially since veins of gold could sometimes be found there… Consequently, numerous stories and beliefs arose concerning riches hidden in the shadows, one of the most enduring of which is that they are made, or gathered, by those humanoid and somewhat unsettling creatures known as goblins. That being said, it is not surprising that a phosphorescent moss growing on the walls of caves has been linked to these mythological figures… We will not delve into the origin of goblins here – a topic that could fill an entire book – but it is worth recalling some of their most famous occurrences. In Germanic countries, they sometimes take on the guise of the Kobold, who can be benevolent towards miners, but also possessive and vengeful when it comes to their precious metal.[xxvi] They are also featured in contemporary culture, for example in the Harry Potter universe, where they once again appear avaricious and fascinated by riches.[xxvii] Guardians of Gringotts Bank, their vaults are scattered throughout underground labyrinths… Of course, they are also encountered in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth, where they dwell in the heart of the mountains. In The Hobbit, Bilbo and his companions thus encounter them in the Misty Mountains, where the treasure guarded by the dragon Smaug is located;[xxviii] another creature associated with our Schistostega, as we have noted.

Up to this point, we can reasonably assume that it was real gold that inspired the folklore, more so than our luminous moss. Certainly, but in some stories, this coveted gold is linked to magical properties that cause it to vanish, or even crumble to dust, when touched… This motif is very interesting for our topic, because it is precisely what happens when one tries to grasp the phosphorescent protonema of the luminous moss: in the light of a torch or lamp, it resembles gold, dazzling… but anyone who scratches the surface and tries to reach the exit finds only dust or earth beneath their fingers, mixed with a rather innocuous little green carpet. Therefore, we can ask ourselves… Could Schistostega pennata have inspired some of these beliefs and legends relating to ephemeral gold, or gold that transforms under the fingers of its discoverer?

The first case, that of disappearing gold, is found in numerous tales, to the point of having been identified as a “classic motif” of folk literature by S. Thompson, under the code N562: “The treasure vanishes of its own accord from time to time / A magical illusion prevents men from seizing the treasures”[xxix]. Often, the said treasure appears only for a very short period, at a symbolic moment on the calendar, and sometimes even at a specific time of day. For example, many underground riches are revealed only on Christmas night, sometimes during Mass or at precisely midnight. Thus, in Maine, a cave inhabited by fairies is accessible only when the church bell in Lavaré rings… Inside, “a heap of gold and silver,” as well as “precious stones that sparkle so brightly they turn night into day,” await the adventurer who dares to enter[xxx]. He can take whatever he wants, but the rock closes again at the last chime of the bell. The phenomenon is similar with the treasure of the Fools of the Allier, accessible only during Christmas Mass or on Palm Sunday, when the priest knocks three times on the church door… but even then, one must have sold one’s soul to the Devil to be able to seize it.[xxxi] Among the other treasures that are revealed at Christmas, we can mention that of the Cave aux Bœufs (in the Sarthe region), or that of the Pyrome rocks (in the Deux-Sèvres region).[xxxii] In some cases, however, the visibility and accessibility of the treasure are even more ephemeral. On the path between Salvan and Fenestral, legend has it that a treasure hidden under a stone is only visible once every hundred years.[xxxiii]

What is interesting about all these stories is that the ephemeral nature of these treasures can echo the reproductive cycle of our luminous moss. The phosphorescent protonema of Schistostega pennata is theoretically observable year-round[xxxiv], but this does not mean that it is perpetually visible at any given site. Thus, we can easily imagine the wonder of a traveler camping in a cave that harbors it, followed by disappointment upon returning months or years later to find nothing dazzling. But beyond the biological cycle of this bryophyte, it is also important to remember that the protonema’s phosphorescence is only perceptible with a specific orientation and intensity of light. In other words, the shimmering effect visible in torchlight disappears when the protonema is moved away from the light source, or when returning in the middle of the day. Furthermore, some Schistostega sites can naturally glow in sunlight at certain times of day, when the sun enters the cave at the right angle. The observer who is lucky enough to be there then sees the goblins’ gold appear… but an ephemeral gold, which disappears in just a few minutes, perhaps inspiring these stories of lost riches.

Within these legends, one last point, and not the least important, deserves our attention: the special moment when these hidden treasures are revealed. This moment generally corresponds to Christmas, which is, of course, a highly symbolic date. That the child-light, Jesus, upon his birth, should bring forth light within the caves is, all things considered, quite logical, and it is understandable that the legends have favored this particular night for this phenomenon. Furthermore, this date also corresponds, more or less, to the winter solstice, which marks the lengthening of the days. Symbolically, it is therefore the advent of light that is celebrated on this date… and its victory over the winter darkness. Now, isn’t this precisely what Schistostega pennata embodies when it twinkles in the heart of the twilight? It represents the glimmer that persists in the heart of the night, like the hope that remains even in the darkest corners of existence. Given its luminous nature, it would not have been surprising if this Bronze Age blacksmith had used it as an emblem of his solar deity, whatever it may have been.

The Treasure That Turns to Dust

That being said, let us return to our modern legends, in which another motif deserves our attention. For while gold sometimes simply disappears, it also frequently turns to dust beneath the fingers of its discoverer, or transforms into mere debris, earth or plant matter. This phenomenon is found in many beliefs, and not only in France. Thus, Mare Kalda, a doctor of philosophy, mentions legends relating to the discovery of a « glow of treasure, » some of which are found in Estonia. In these stories, people gathered around a fire may receive earth or coals to light their pipes… which ultimately turn out to be gold after some time. But the opposite phenomenon is at least as widespread: the treasure passed on transforms into a substance that ultimately has no value: earth, leaves, ashes[xxxv]… Is it because the fire around which the gathering was held went out? The luminous moss was goblin gold as long as the flames made its protonema sparkle, but it became tiny moss embedded in earth once night fell.

This same motif appears in the North American tale « The Crumbling Silver. » It tells of shining nodules on the rock, which arouse the covetousness of a man named Gardiner. Unwilling to share anything with anyone, he ends up killing the Montauks Indian who had shown him the spot… but in doing so, he unleashes a curse. Returning home by candlelight, he discovers that what he has taken no longer shines as it should. The next morning, in his cellar, he finds only a pile of gray dust flecked with a few coppery reflections[xxxvi]… The treasure has been transformed into a worthless thing. It no longer shines, like the protonema of Schistostega brought into the light of day, or by the light of a poorly positioned lamp. Thus, the precious object that deteriorates and ceases to shine is an intercultural motif, found from Estonia to the United States. Of course, it is also encountered in Western Europe, for example in connection with the famous leprechauns. Their treasure is reputed to be unattainable, protected by enchantments and well-kept secrets. If by chance someone manages to seize it, it can transform into leaves, into earth, or simply disintegrate at lightning speed, especially if certain rules are not followed (do not raise your voice, do not look back, do not reveal the location…). The same is sometimes true of the fairies’ hoardings, or even of the riches that witches believe they obtain from the devil. In many witchcraft trials, the person seduced by the Devil receives a kind of payment in exchange for their soul, in the form of gold or coins. But generally, this money ends up disappearing, or more precisely, transforming into something worthless; sometimes earth, but more often oak leaves.[xxxvii]

This motif of gold that metamorphoses once taken is found in a tale by the Brothers Grimm: « The Gifts of the Little People. » A tailor and a goldsmith, traveling in the dead of night, discover a gathering of merry elves, join them, and obtain coal from them, filling their pockets. The next morning, waking up in an inn, the two companions are pleased to find that it has turned into gold… But the story doesn’t end there, for the goldsmith then decides to find the little people again to obtain even more of their gold. As the reader will have guessed, his greed is punished, and the coal remains coal this time. Worse still, the gold he initially obtained has also reverted to mere scrap.[xxxviii] Contemporary literature has also seized upon this concept. For example, in his short story « The Devil and Tom Walker, » Washington Irving features an individual to whom a mysterious figure reveals the location of Captain Kidd’s treasure. Since the treasure is cursed and protected by the devil himself, the man becomes rich at the expense of his soul, but ultimately ends up ruined by a supernatural process in which the gold and silver he had unearthed are transformed into wood chips.[xxxix]

A similar phenomenon occurs in the English folktale « The Hedley Kow« , but with a more favorable outcome for the protagonist. An old woman finds a pot filled with gold, but on her way home, glancing inside, she realizes the gold has turned into silver. A little later, she notices the pot contains iron, then rock. Yet, the woman takes each of these transformations with optimism, even when the pot’s contents finally become the Hedley Kow, a strange, mischievous little creature that runs away laughing. She considers herself lucky to have witnessed such a supernatural being and returns home pleased with her good fortune[xl]… much like bryologists discovering Schistostega by the light of their flashlight. True treasures, ultimately, are never material.

The fact remains that the motif of ephemeral gold, or gold that turns out to be nothing more than a worthless heap of debris, is actually extremely common in the collective imagination. Often, wealth is merely an illusion, temporary, like the protonema of Schistostega pennata, which appears as gold in illuminated caves but becomes hopelessly ordinary once brought into the light of day… at least for those unfamiliar with bryology. In Gascony, it was said that gold was likely to rot and turn red underground, so goblins had to display their treasure at the entrance of caves for an hour on New Year’s Eve to ensure it retained its full luster.[xli] The mention of the color red is interesting when one considers that it often characterizes sandstone, a favorite habitat of bioluminescent moss. The species is also present in Gascony, which leads us to highlight another interesting aspect of all these beliefs and legends: their location.

Indeed, by examining these tales of ephemeral gold or treasure that transforms once taken, we find that many of them originate from regions where goblin gold is actually known. This is the case in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques, certainly, but also in Brittany and Wales, territories renowned for their legends relating to the Little People. It should be noted, however, that the species is absent from Ireland, that is to say, the original homeland of leprechauns, even though the creature has subsequently become part of the imagination of other countries. Furthermore, the species is present in Estonia, Scotland, and also in the majority of the northeastern states of the United States.[xlii] It is also found in Northumberland, England, the origin of the legend of The Hedley Cow[xliii].

It is also found in southern Germany, particularly in the Fichtelgebirge (a mountain range in northeastern Bavaria), where folklore mentions strange elf-like figures entirely covered in moss, including a famous « moss lady » who may appear to hikers. In one of the legends associated with her, the creature asks for the strawberries that a little girl picked for her sick mother, which the mother agrees to. Upon returning home, however, the little girl discovers that her basket is now filled with golden strawberries… But it is not so much the story itself that interests us as the description sometimes given of this “foam lady,” if we are to believe Richard Folkard: “The little woman’s moss dress is described as being golden in color, which shone, seen from a distance, like pure gold, but which, up close, lost all its luster”[xliv]. In other words, this fairy’s garment sparkles when viewed from a certain angle… but becomes dull upon closer inspection. We can even imagine that the moss lady is luminescent as long as she remains in the dim light of the fir trees or the rocks, but that she loses her glow when she reveals herself in the daylight, for example, when she moves into the clearing to meet the walker… In any case, we can legitimately wonder if her attire might not be made up – at least in part – of Schistostega pennata… even if other plant species have been suggested, such as clubmosses. Folkard, moreover, writes something about them that could also apply quite well (and perhaps even more so) to the luminous moss: “It is thought that many of the stories of hidden treasure circulating about the Fichtelgebirge are due to the presence of this curious plant species in the massif”[xlv].

That being said, the purpose of this article is by no means to claim that all these legends and beliefs stem directly from the luminous nature of Schistostega pennata. They may well have been inspired by many other natural phenomena, of course, as well as by psychological, philosophical, or even moral considerations. These tales bear witness to humanity’s age-old obsession with hidden riches and its fear of seeing acquired wealth vanish. They also illustrate the dangers of reckless greed by punishing the avaricious. Finally, these stories often highlight the illusory nature of earthly riches, which spiritual values ultimately supersede. Nevertheless, it is striking to note how perfectly the phosphorescent phenomenon of the protonema of our moss, which disappears in daylight, fits these motifs. Therefore, it is not out of the question that some local stories may have been inspired by these unsettling observations. by this luminous moss within remote caves, which became nothing more than soil once removed. In any case, it is highly improbable that such an extraordinary phenomenon would not have stimulated the human mind… How can one imagine children remaining stoic while exploring a cave by torchlight, surrounded by patches of phosphorescent emerald green? Little by little, through word of mouth, these observations could become rumors, then, in the hands of a storyteller, transform into a tale, ultimately amended and distorted over the centuries until it reaches us…

CONCLUSION

Schistostega pennata is therefore a truly extraordinary bryophyte. The luminescent property of its protonema has endowed it with a unique place in the human imagination, which is expressed in various ways. Its etymology, first of all, testifies to the fantastical dimension it inspires: rabbit candle, goblin gold, dragon gold… It must be said that the species, shining at the entrance of caves like a hidden treasure, creates all the conditions for an epic adventure for the bryologists who discover it, as we can see from the enthusiastic accounts they have given us. That being said, the luminous moss doesn’t just move naturalists: it also inspires in ordinary people a veneration expressed through films, video games, and even monuments erected in its honor. Finally, we might even wonder if it hasn’t inspired certain legends and popular beliefs, particularly those relating to ephemeral treasures or those that crumble to dust… In any case, Schistostega pennata is a treasure in itself, and one of the most beautiful there is. She is a marvel of nature, a touch of magic in this world. Anyone lucky enough to observe her receives a lucky talisman, which will accompany them wherever they go, nestled deep in their heart, and which is therefore infinitely more precious than all the chests filled with diamonds.

Pablo Behague. « Sous le feuillage des âges ». Novembre 2025.

[i] Isabelle Charissou, 2015, La mousse lumineuse Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) F. Weber & D. Mohr en France et en Europe, vol. 45, Bulletin de la Société botanique du Centre-Ouest.

[ii] Charissou, 2015, op. cit.

[iii] Leonard Thomas Ellis et Michelle Judith Price, 2012, Typification of Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) F.Weber & D.Mohr (Schistostegaceae), vol. 34, Journal of Bryology.

[iv] Sean R. Edwards, 2012, English Names for British Bryophytes, British Bryological Society, British Bryological Society Special Volume.

[v] USDA Forest Service, s. d., Gotchen Risk Reduction and Restoration Project.

[vi] Arne A. Frisvoll et al., 1995, Sjekkliste over norske mosar, Norsk institutt for naturforsking.

[vii] Martin Nebel et Georg Philippi, s. d., Die Moose – Baden-Württembergs, Ulmer, vol. 2.

[viii] C. Casas et al., 2000, Flore Briofitica Iberica. Referencas Bibliograficas., Institut Botanic de Barcelona, vol. 17.

[ix] Edwards, 2012, English Names for British Bryophytes, op. cit.

[x] royvickery, 2016, QUERY: Rabbit’s candle, plant-lore.com.

[xi] Edwards, 2012, English Names for British Bryophytes, op. cit.

[xii] J.M. Glime et Magdalena Turzanska, 2017, Bryophyte Ecology – Light : Reflection and Fluorescence, Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists.

[xiii] Lunds Botaniska Forening, 2001, Botaniska notiser, vol. 134‑1.

[xiv] Anton Kerner von Marilaun, 1863, Das Pflanzenleben der Donauländer.

[xv] George B. Kaiser, 1921, Little journeys into mossland, IV : Luminous moss., vol. 24, Bryologist; Charissou, 2015, La mousse lumineuse Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) F. Weber & D. Mohr en France et en Europe, op. cit.

[xvi] royvickery, 2016, QUERY: Rabbit’s candle, op. cit.

[xvii] Hisashi Nogami et Aya Kyogoku, 2020, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, Nintendo.

[xviii] Taijun Takeda, 1953, Hikarigoke (Mousse lumineuse).

[xix] Ikuma Dan et Taijun Takeda, 1972, Hikarigoke (Mousse lumineuse) – Opéra.

[xx] Kei Kumai et Taijun Takeda, 1992, Hikarigoke (Mousse lumineuse) – Film.

[xxi] James Holms Dickson, 1973, Bryophytes of the Pleistocene: the British record and its chorological and ecological implications, Cambridge University Press.

[xxii] Ian D.M. Atherton, Sam D.S. Bosanquet, et Mark Lawley, 2010, Mosses and liverworts of Britain and Ireland – a field guide, British Bryological Society.

[xxiii] Dickson, 1973, Bryophytes of the Pleistocene: the British record and its chorological and ecological implications, op. cit.

[xxiv] Dickson, 1973, op. cit.

[xxv] Tim Holt-Wilson, 2013, Our Vital Earth : Goblin’s Gold, storvaxt.blogspot.com.

[xxvi] Rossana Berretta, Ilaria Spada, et Amedeo De Santis, 2007, Les créatures fantastiques, Piccolia.

[xxvii] J.K. Rowling, 1997, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Bloomsbury.

[xxviii] J.R.R. Tolkien, 1937, The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, George Allen&Unwin.

[xxix] S. Thompson, 1955, Motif-index of folk-literature : a classification of narrative elements in folktales, ballads, myths, fables, medieval romances, exempla, fabliaux, jest-books, and local legends., Bloomington : Indiana University Press.

[xxx] Paul Sébillot, 1904_1907, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France – Le folk-lore de France, E. Guilmoto, Omnibus.

[xxxi] Sébillot, 1904_1907, op. cit.

[xxxii] Sébillot, 1904_1907, op. cit.

[xxxiii] Sébillot, 1904_1907, op. cit.

[xxxiv] Charissou, 2015, La mousse lumineuse Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) F. Weber & D. Mohr en France et en Europe, op. cit.

[xxxv] Kalda, Mare, 2014, Hidden Treasure Lore in Estonian Folk Tradition, EKM Teaduskirjastus; Mare Kalda, 2023, Reality as Presented in Estonian Legends of Hidden Treasure, Yearbook of Balkan and Baltic studies.

[xxxvi] Auteur inconnu, 2021, The Crumbling Silver (North American Folk Tale), en. derevo-kazok.org, Fairy Tales Tree.

[xxxvii] Philippe Jéhin, 2002, Les aveux d’une sorcière en 1619, Dialogues transvosgiens; Maurice Foucault, 1907, Les procès de sorcellerie dans l’ancienne France devant les juridictions séculières, Bonvalot-Jouve; Alexandre Tuetey, 1886, La sorcellerie dans le Pays de Montbéliard, A. Vernier-Arcelin; Frédéric Delacroix, 1894, Les procès de sorcellerie au XVIIe siècle; Charles-Emmanuel Dumont, 1848, Justice criminelle des duchés de Lorraine et de Bar, du Bassigny et des trois évêchés.

[xxxviii] Jacob Grimm et Wilhelm Grimm, 1850, Les Présents du peuple menu, Kinder- und Hausmärchen – Contes de l’enfance et du foyer.

[xxxix] Washington Irving, 1824, The Devil and Tom Walker, John Murray.

[xl] Joseph Jacobs, 1894, The Hedley Kow, More English Fairy Tales.

[xli] Sébillot, 1904_1907, Croyances, mythes et légendes des pays de France – Le folk-lore de France, op. cit.

[xlii] Charissou, 2015, La mousse lumineuse Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) F. Weber & D. Mohr en France et en Europe, op. cit.; Departement of Natural Resources, Rare Species Guide – Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) Web. & Mohr (www.dnr.state.mn.us, 2025).

[xliii] Atherton, Bosanquet, et Lawley, 2010, Mosses and liverworts of Britain and Ireland – a field guide, op. cit.

[xliv] Richard Folkard, 1884, Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics.

[xlv] Folkard, 1884, op. cit.