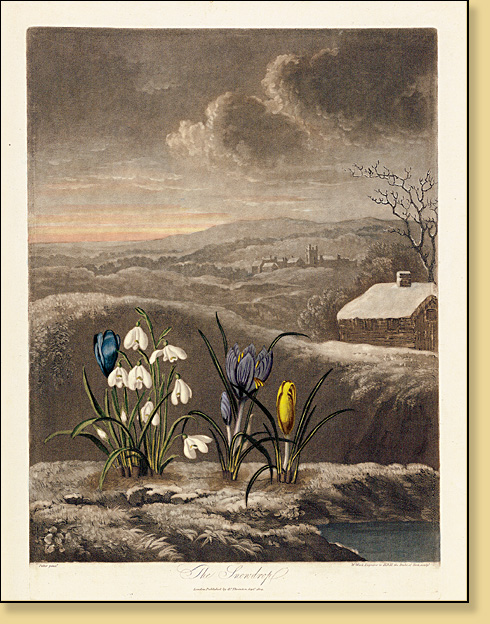

While winter is not quite over and snow still covers the landscapes, small white bells are emerging from the dust along the paths, putting an end to the impatient botanist’s wait, who watched for the first blooms during his walks. Of course, what is depicted here is the season of the snowdrops, a term that has long been ambiguous since it could refer to both Leucojum and Galanthus. Nevertheless, these species share a certain affinity, which appears extremely clear on a symbolic level.

In the popular imagination, indeed, snowdrops embody the end of winter and the beginning of spring, or more precisely, the duality that exists between the two seasons. They are the flowers of transition and renewal, of the cold period diluting into the mild air of March, of the passage from death to life… But the symbolism of these plants is far from being so monolithic, since they have also been made emblems of virginity or even funerary omens. It has even been suggested that they could correspond to a mysterious plant from ancient mythology endowed with fabulous powers, and which Odysseus consumes before entering Circe’s house…

Flowers of winter and spring

The primordial symbolism of snowdrops, in the broadest sense, intimately associates them with winter and, a fortiori, with the snow that characterizes it. In this regard, examining their etymology is rich in lessons, and offers us many illustrations of this relationship. The common term « snowdrop » speaks for itself, but we know of other less widespread and equally evocative slang names for them. Thus, Galanthus nivalis is sometimes called « Winter Galantine, » « Winter Bell, » or even « Snow Galanthus. » In some cases, regional languages take up this concept of a flower making its way through the white layer, as in Normandy where we speak of « Broque neige » or in Brittany where we evoke the « Treuz-erc’h. » As for European countries, many also use a term that is a translation of our « snowdrop » as in Yorkshire, England, where the plant is called « snowpiercer » (1). Among the other English names that we know of it, we can cite for example « winter gallant », « snowdrop » or even « little snow bell » which therefore relates to snow (2). As for Leucojum, their most commonly accepted name is that of « snowflake ».

The scientific names for snowdrops are just as relevant to all these winter notions. Galanthus can be translated as « milk flower. » As for the adjective nivalis, it obviously means « of the snows. » Thus, snowdrops are literally « milk flowers of the snows, » an expression that refers not only to their immaculate whiteness, but also to their flowering season. Leucojum is constructed from the word leuko, meaning « white, » and the word ion, which corresponded to violets. In other words, snowdrops are « white violets. »

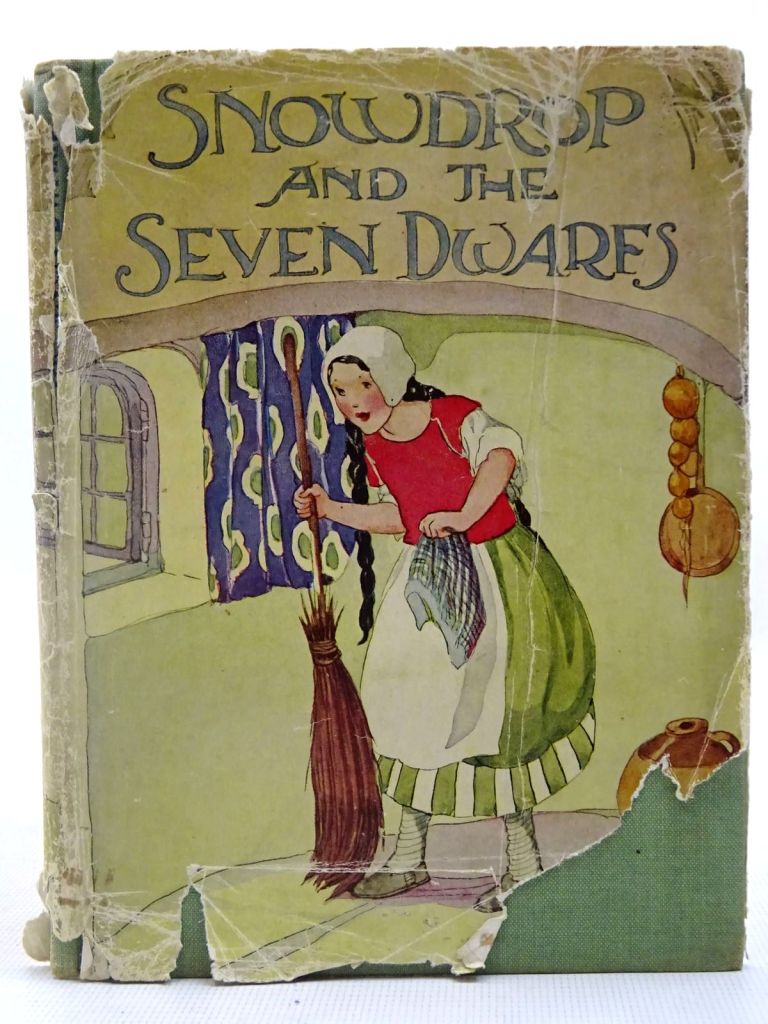

One of the oldest references to the term « snowdrop » dates back to a manuscript dated 1641, Guirlande de Julie, which once again emphasizes the plant’s winter dimension. The poem dedicated to her includes these lines: Under a silver veil the buried Earth / Produces me despite its freshness / The Snow preserves my life / And giving me its name gives me its whiteness (3). Subsequently, the term was used in relation to figures linked either to the notion of winter or to the notion of whiteness. Thus, the character of Snow White, from the famous tale by the Brothers Grimm, has sometimes been translated as « Snowdrop » (4). We will have the opportunity to return to this. This name is also that of Dinah’s kitten, Alice’s cat in the work of Lewis Carroll. Unsurprisingly, the passages that mention it evoke its white coat, the little girl even allowing herself to call it « White Majesty » (5). From then on, we see a clear affiliation, both ecological and symbolic, between snowdrops and winter.

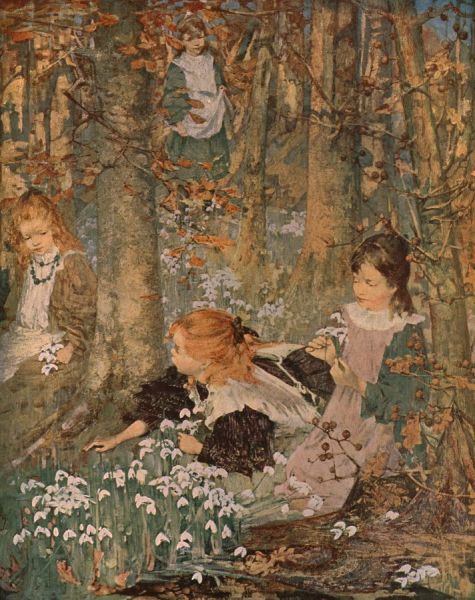

However, while Galanthus and Leucojum are indeed linked to winter, they primarily embody the end of winter. Indeed, when snowdrops break through the snow, it signifies the arrival of spring. They are, in a way, the scouts of the warm season, poking the tips of their bells through the icy layer before signaling the arrival of other vernal flowers such as primroses and violets. Therefore, it is not surprising that the etymology of these plants is also linked to spring and the return of fine weather. Thus, one of the snowdrops found in our region is the Spring Snowflake, which its scientific name indicates with the use of the word vernum. One of his English names is « spring whiteness » (6).

In fact, when these white flowers are mentioned, it is very often to emphasize the spring-like nature of the atmosphere. Snowdrops and snowflakes are, for the reader, an indicator of spring, a temporal marker situated precisely at the end of winter. In The Butterfly, Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, the insect is looking for a flower to marry. The author then explains to us that « it was the first days of spring », which naturally implies that « crocuses and snowdrops were blooming nearby » (7). It is also interesting to note that these two flowers are often associated in an initial procession, as in Goethe who in the poem Next Year’s Spring writes: « The beautiful snowdrops / Unfold in the plain / The crocus opens » (8). Théophile Gautier, in a poem entitled Premier sourire du printemps (First Smile of Spring), tells us about Mars preparing for the arrival of fine days: “While composing solfeggios / Whistling to the blackbirds in a low voice / He sows snowdrops in the meadows / And violets in the woods” (9). It is again with the violet that our flower is associated in The Prince of Thieves, attributed to Alexandre Dumas. We find a monk reading a note from a young girl to her lover: “When the less harsh winter allows the violets to open / When the flowers are in bloom and the snowdrops announce spring / When your heart calls for sweet glances and sweet words / When you smile with joy, do you think of me, my love?” (10). In Little Ida’s Flowers, Andersen – him again – this time associates our plant with the hyacinth, another spring species: « The blue hyacinths and the little snowdrops rang as if they carried real bells » (11). Let us conclude this spring review of the snowdrop by quoting two extracts from the Chronicles of Narnia, a famous fantasy saga. In the first volume, the children see winter suddenly disappear, by magic. And what better way to characterize such an extraordinary phenomenon than by mentioning snowdrops? The author is not mistaken, since he tells us that after crossing a stream, they come face to face with snowdrops growing (12)…

The connection between these plants and the return of the warmer weather is therefore clear, and it is not surprising that they are used in the Martisor festival in Romania, celebrated in March. This connection is also expressed through several fascinating legends featuring the character of the « Spring Fairy. » In one of them, we see her confront the « Winter Fairy, » ultimately winning in single combat. From a drop of blood from the defeated fairy, the snowdrop is born, symbolizing the victory of the warmer weather over that of death (13). In another story, the Spring Fairy comes to the aid of a small snowdrop frozen by the icy winter wind. She clears the snow covering it and restores its life with a drop of blood (14).

More generally, snowdrops are linked to the idea of beginning and renewal, obviously springtime values. We thus find the snowdrop in a primitive legend featuring Eve, just banished from paradise and wandering on the desolate earth. The snow was falling, laying a shroud over the world condemned by the fall of Man. An angel therefore descended to console the first woman. He took a snowflake and blew on it, ordering it to bud and blossom, which of course immediately gave birth to a snowdrop. Eve then smiled, understanding the symbol of hope that the flower represents (15). It embodies renewal in the heart of darkness, the light at the end of the tunnel. It is also a symbol of consolation, which contemporary authors also note.

A symbol of remembrance, the snowdrop is also dedicated to Saint Agnes, herself associated with the phoenix. Both the mythological bird and the flower are capable of being reborn from the darkness, of springing forth from the ashes of death and winter. They embody the hope of life even in the heart of darkness.

A symbol of virginity and purity

Closely linked to whiteness and the concept of beginning, as we have just seen, it is quite natural that the snowdrop is also associated with the notion of virginity and purity. Once again, etymology is rich in lessons on this subject, and already allows us to get a clear idea of this facet of the plant. In England, Galanthus nivalis is sometimes called Mary’s tapers (16). This of course refers to the well-known Virgin, mother of Jesus, which the use of another name, that of Virgin flower, seems to support (17). In fact, snowdrops are even explicitly dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and a Christian legend has it that their flowering takes place precisely on February 2, the day of Candlemas during which the mother of Jesus took him to the Temple to make an offering. This anecdote also justifies another popular name for the plant, Fair Maid of February (18). Richard Folkard also points out that « the snowdrop was once considered sacred to virgins, » which, according to him, « may explain why it is so commonly found in orchards attached to convents and ancient monastic buildings » (19). Thus, nuns would have sown snowdrops abundantly around their retreats, as symbols of their chastity. Thomas Tickell, an 18th-century English poet, supports this view, speaking of a « flower that smiles first in this sweet garden, sacred to virgins, and called the Snowdrop » (20).

This connection to the virginity is not unique to Christianity, which makes it all the more interesting. Indeed, the snowdrop is closely linked to young girls in many traditions and tales. During the spring celebrations held at the beginning of March, Matronalia among the Romans or Martisor among the Romanians, the flower is often offered to young ladies. Furthermore, the snowdrop is linked to several female figures of virginity, one of the most famous of which is none other than Persephone. Let us recall that in the most famous myth concerning her, the young girl is abducted by Hades while picking flowers in a meadow, and taken to the underworld. While the snowdrop is never mentioned in ancient sources, Ovid himself mentions « the violet or the lily » (21). However, we have seen to what extent our snowdrop was often linked to the violet. In any case, later traditions have clearly associated Persephone with the snowdrop. Is this really surprising, given that this flower is a symbol of spring and renewal? Demeter’s daughter, in fact, embodies precisely this idea of an annual vegetative cycle. An agreement is concluded, under the aegis of Zeus, which allows her to spend half the year in the open air, but obliges her to remain the rest of the time with her husband, in the underworld. From then on, Persephone emerges from the earth like the flowers of spring, emerging at the beginning of March like snowdrops. This link between the goddess and the plant is also found in a contemporary song, composed by the rapper Dooz-Kawa and entitled Perce neige: “Yeah, this rain that cries in the autumn that loses its fauns / It’s Demeter who is dying of Persephone’s exile / In short, we are snowdrop flowers, the ultimate weapon of distress / Drops that flow like the tears of the goddess” (22).

The myth of Persephone shares some similarities with the tale of Snow White, whose name, as we have seen, has sometimes been translated as « Snowdrop » (23). Like the Greek goddess, Snow White is a young girl subjected to the assaults of infernal forces, in this case a witch-stepmother. Like her, she symbolically undergoes a winter « eclipse, » falling into a long sleep that is only broken by the prince’s kiss, an allegory of spring that revives vegetation… and first and foremost the snowdrop. Thus, Persephone and Snow White can be seen as personifications of the beautiful season, but also of the plant that interests us, forging a path from the depths to bring blossom to the world.

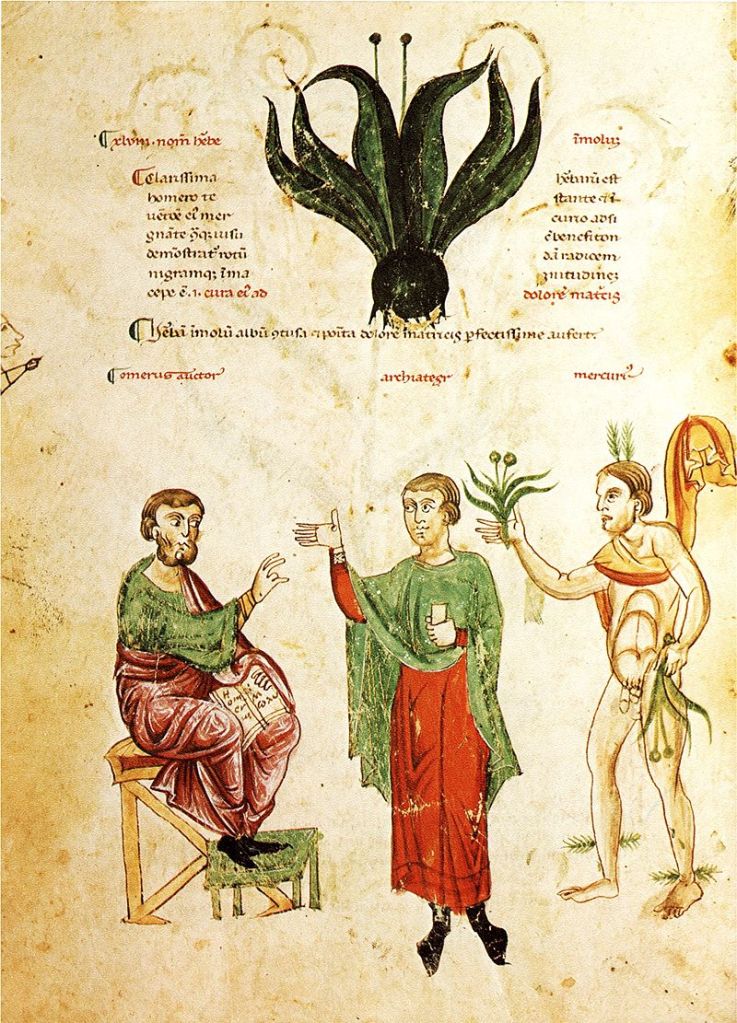

The snowdrop heralds the time of rural frolics, the joyous period of youthful love in which young people indulge. A song from 1860 attests to this, with poetry typical of the century: “Watch over your little roses / The snowdrop will shine! (…) / You whose white muslin / Betrayed the pretty contours / In winter, under the Levantine / You close the door to love / Of happiness, sweet messengers / Let modesty slumber / Take up your light dresses / The snowdrop will shine” (24). We therefore see our plant clearly subservient to young ladies, and this symbolic association perhaps explains the medical properties attributed to it in old manuscripts. Indeed, Dioscorides, the famous physician of Antiquity, believes that the dried flowers of the snowdrop “are good for bathing the inflammation around the uterus and expelling the menstrual flow”. The plant thus presents a very clear feminine character and is linked to figures of purity, of which the Virgin Mary is the most emblematic example.

From Funeral Oblivion to Homer’s Moly

Yet, contrary to our current understanding of the plant, snowdrops have also been interpreted as funerary symbols. Is this because of their white color and their connection to snow, evoking the shroud of mortuary chambers? The fact remains that several beliefs and traditions lead us to this register of mourning and death.

In certain regions of England, for example, it is believed that the first snowdrop of the year should not be brought inside homes. It is said to bring bad luck and could attract the grim reaper into the home. This belief stems from the flower’s resemblance to a corpse in its shroud, but the symbolism of winter undoubtedly plays a role as well (25). The same idea implies that one should never give someone snowdrops, because that would mean that one wants them dead. An English legend also tells of a woman who discovers her lover seriously injured and decides to place snowflakes on his wounds. These then turn into snowdrops at the same time as the man dies (26).

But our plant’s relationship with death is also illuminated by its properties. Snowdrops are, in fact, toxic plants, and even fatal in relatively small doses. In the 19th century, François-Joseph Cazin explained that this toxicity was discovered accidentally when a woman sold snowdrop « onions » instead of chive ones (27). This reportedly caused violent vomiting in consumers, a classic symptom of poisoning from the plant’s bulb.

However, as is often the case, a poisonous herb can also, when carefully dosed, become a valuable medicine. This is the case with snowdrops. Galanthus nivalis contain galantamine, which is used to combat cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease or any other memory-related disorder (28). It is therefore no coincidence that the snowdrop was chosen as the emblem and name of a charity helping people affected by mental illness, founded by Lino Ventura and his wife Odette in 1966. Furthermore, galantamine is said to be an antidote capable of counteracting the effects of certain drugs, particularly atropine, contained in many nightshades used in witchcraft. This last point leads us to a fascinating historical mystery: that of a plant cited by Homer in the Odyssey, which he calls moly.

While Homer is the first to mention this plant, other ancient authors who came after him also did so, attempting to identify species familiar to them, such as Theophrastus (29), Dioscorides (30), Pliny the Elder (31), and Pseudo-Apuleius (32). However, several arguments support our snowdrop, in the broadest sense of the term. Indeed, the moly is mentioned when Odysseus and his companions, during their journey to Ithaca, visit Circe’s island. The episode is well known: the crew sent to reconnoiter the sorceress’s lair is transformed into a herd of pigs, with the exception of Eurylochus, who brings the news to Odysseus. Odysseus then sets out to free them and as he advances, he meets the god Hermes, who offers him his advice. It is at this moment that the moly is mentioned: « Here, take, before going to Circe’s house, this good herb, which will drive away the fatal day from your head. I will tell you all Circe’s evil tricks. She will prepare a mixture for you; she will throw a drug into your cup; but, even so, she will not be able to bewitch you. » for the good herb, which I am going to give you, will prevent its effect » (33). By following the advice of the messenger god, Ulysses actually manages to outwit the poison and save his companions.

The significance of this episode is much more complex than it appears, and upon reading it, it is easy to understand why researchers have suggested that moly could correspond to our snowdrop (34). First of all, Circe is a sorceress, a witch, and there is no doubt that the mixture she prepares includes toxic ingredients, capable of making sailors lose their minds. The famous transformation into a pig, in fact, presents all the characteristics of a psychotic delirium. Individuals begin to hallucinate and act like animals, abandoning their humanity under the influence of the drug. From then on, we are entitled to suggest that the potion concocted by Circe included some well-known nightshades, such as deadly nightshade, nightshade, mandrake, or even the fearsome datura. Now, have we not observed that the galantamine of the snowdrop is capable of combating the symptoms of atropine? The herb picked by Hermes and offered to Odysseus could then be our plant, capable of countering Circe’s magic.

But the arguments in favor of a snowdrop moly don’t stop there, since Odysseus’s companions, upon entering the cursed dwelling and transforming into pigs, experience an episode of obvious mental disorder. Allegorically, this metamorphosis corresponds to amnesia, a forgetting of one’s own person and humanity… All signs of madness that the snowdrop is able to counteract through its effect on memory and the brain. Odysseus keeps his head on his shoulders when his men lose it, but it is with the moly that he cures the madness and forgetfulness of his comrades. It is also interesting to note that the species is mentioned in video games related to the Harry Potter universe (35). However, according to the Pottermore website, moly is mentioned in the book A Thousand Magical Herbs and Mushrooms by the witch Phyllida Augirolle, where it is stated that it combats enchantments.

Let us note in conclusion that ancient descriptions of the plant, although absent from Homer, support the hypothesis of the snowdrop or snowflake. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, speaks of a « white flower, which has a black root » that Odysseus uses as a talisman upon entering Circe’s home (36). It must be said that symbolically, by appearing first after the winter darkness, the snowdrop is a marker of memory; it reminds us of the existence of spring and fine weather, just as the moly reminds the members of the transformed crew who they really are.

****

Thus, snowflakes and snowdrops conceal many mysteries. They symbolize the whiteness of winter, and are therefore linked to notions of virginity and purity. From Mary to the spring fairies, from Persephone to Snow White, these early-blooming plants are also associated with the return of light to the heart of darkness; with renewed hope after long winter nights. In a way, the snowdrop « drives away the cold winter, » as the well-known folk song invokes. « Drive the Cold Winter Away » dates back to at least the 17th century (37), a time when winter was experienced in the flesh and was a difficult ordeal to grasp in the light of our modern comforts. Seeing the snowdrop’s bell must have warmed the heart of the peasant, whose reserves were perhaps running low.

But the snowdrop also symbolizes remembrance. It reminds us of the existence of sunny days and festive springs at a time when the tunnel of winter seems endless. Furthermore, it is perhaps the famous moly mentioned by ancient sources, including Homer, who counteracts the magic of forgetting perpetrated by Circe. As I finish this article, the snowdrops have emerged on the roadsides and in the gardens still covered in the morning frost. Scouts of the spring procession, they will soon be followed by violets, primroses and other hyacinths… then fall back into their annual sleep, without being forgotten.

Pablo Behague, « Sous le feuillage des âges ». Février 2025.

_________

(1) Richard Mabey, 1996, Flora Britannica.

(2) Charles M. Skinner, 1911, Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits and Plants : In All Ages and in All Climes.

(3) Auteurs incertains, 1641, Guirlande de Julie.

(4) Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm, et Arthur Rackham, 1909, The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm.

(5) Lewis Carroll, 1865, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

(6) Skinner, 1911, Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits and Plants : In All Ages and in All Climes., op. cit.

(7) Hans Christian Andersen, 1861, Le Papillon.

(8) Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1816, Next Year’s Spring.

(9) Théophile Gautier, 1884, Premier sourire du printemps.

(10) Alexandre Dumas, 1872, Le Prince des voleurs.

(11) Hans Christian Andersen, 1835, Les fleurs de la petite Ida.

(12) Clive Staples Lewis, 1950, The Chronicles of Narnia – The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

(13) 2020, Le perce-neige : mythe, légende et remède, murmuresdeplantes.fr.

(14) 2010, Légendes du perce-neige, beatricea.unblog.fr.

(15) Richard Folkard, 1884, Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics.; Skinner, 1911, Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits and Plants : In All Ages and in All Climes., op. cit.

(16) Mabey, 1996, Flora Britannica, op. cit.

(17) Skinner, 1911, Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits and Plants : In All Ages and in All Climes., op. cit.

(18) Folkard, 1884, Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics., op. cit.

(19) Folkard, 1884, op. cit.

(20) Thomas Tickell, 1722, Kensington Garden.

(21) Ovide, Ier s., Métamorphoses.

(22) Dooz Kawa, 2014, Perce Neige.

(23) Grimm, Grimm, et Rackham, 1909, The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm, op. cit.

(24) Jean-François Dumas, 2014, Le perce-neige (Galanthus nivalis) et espèces proches.

(25) Folkard, 1884, Plant Lore, Legends and Lyrics., op. cit.

(26) Skinner, 1911, Myths and Legends of Flowers, Trees, Fruits and Plants : In All Ages and in All Climes., op. cit.

(27) François-Joseph Cazin et Henri Cazin, 1868, Traité pratique et raisonné des plantes médicinales indigènes.

(28) Jacqueline S. Birks, 2006, Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease.

(29) Théophraste, IVe-IIIe s. av. J.-C., Historia plantarum – Recherche sur les plantes.

(30) Pedanius Dioscoride, Ier s., De Materia Medica.

(31) Pline l’Ancien, vers 77, Histoire naturelle – Livre XXI.

(32) Pseudo-Apulée, IVe s., Herbarius.

(33) Homère, VIIIe s. av. J.-C., L’Odyssée.

(34) Andreas Plaitakis et Roger C. Duvoisin, 1983, Homer’s moly identified as Galanthus nivalis L.: physiologic antidote to stramonium poisoning.

(35) Jam City, 2018, Harry Potter : Secret à Poudlard – jeu.

(36) Ovide, Ier s., Métamorphoses, op. cit.

(37) Auteur inconnu, 1625, Drive the Cold Winter Away – chanson.

You can follow my news on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sous.le.feuillage.des.ages/